If you ever want to stump someone with a trivia question about the Episcopal Church, ask them “What is our only major feast that celebrates a teaching?” The answer is this one: Trinity Sunday. It’s a terrific day because we get to focus on who God is – a question so important, and so determinative of how you live your life, that we don’t want to get it wrong. Sometimes church folks talk about the Trinity with a kind of embarrassment, as if the concept were an obscure, non-essential matter along the lines of arguing over how many angels can dance on the head of a pin or whether to use violet or blue hangings in Advent. Even some clergy joke about how arcane the Trinity is, and how they wish they didn’t have to preach today – which is something I really don’t get. You’re clergy, and you don’t want to talk about who God is? What do you want to talk about? God isn’t exactly an optional extra. But you do hear this feast referred to that way – as if there were something generic that everyone agreed on called “God,” and then Christianity sort of stuck a few extra ideas on top and came up with the Trinity. If we took a moment to look back and figure out where that habit came from, historically, we could probably trace it to the 18th century, during the Enlightenment era. In fact, when the American Book of Common Prayer was revised in 1789, one group actually proposed removing all references to the Trinity from Episcopal liturgy. The 18th century was a period of optimism about human nature and human perfectability, so no wonder it favored a theology based on things humans figured out. Because surely we were smart enough to reason our way to anything worth knowing, right? All those old claims that God had revealed truths to us – weren’t they just unnecessary supernatural icing on a natural cake, or maybe even power grabs by an elite? In the climate of the Enlightenment, it became fashionable to downplay the idea of God's revelation and prioritize talking about what people could come up with for themselves.

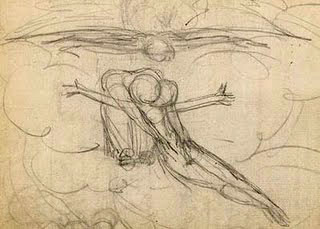

We’ve had a couple centuries of the after-effects of that choice now, and it seems to me that what people tend to come up for themselves has gotten pretty shopworn. And in fact there’s been a major resurgence of Trinitarian theology in the past few decades, now that the church has really begun to experience the cost of having avoided talking about our most central and most distinctive ideas for so long that people don’t really know for sure what those ideas are anymore. Or worse, they think they know, but actually don’t. I’ve done some college chaplaincy here and there, and -- especially as I was just starting out in the 90s, when Christianity still had a residual hold on American culture and more people had some background in some church growing up – back then, students would inform me that they didn’t believe in God, and I would usually ask them to tell me about the God they didn’t believe in, and the God they had come up with would almost invariably be a God about whom, as a Christian, I had to say “I don’t believe in that God either.” The God they described was never the God who revealed himself in Scripture, never the merciful, beautiful Trinity whose very nature is relationship. It was never the God who was so determined to let us in on his unlimited love that he would limit himself, taking finite flesh and dying and rising for us in Jesus so that we could eat and drink divine life. The God they didn’t believe in wasn’t our Triune God who has never been alone, but has always lived as a vulnerable, self-giving community. It was usually a sort of remote, solo, untouchable monarch. Isolated, self-centered, unchanging, single-handedly in charge, requiring tribute and expecting you to be on your best behavior, watching you and judging you from on high, out of touch with the human heart, and really into power. At best, that concept is un-relatable, and at worst, something rather more sinister. If that were what Christians meant by the word God, I completely understand Christopher Hitchens saying that believing in God must be like living in North Korea. I’m not sure I would hear that same kind of description of God offered if I asked today. Because that concept is fading, I think, in favor of another one people come up with for themselves. Please tell me if you think this is atypical, but in my experience the sort of all-powerful old man on a throne misunderstanding seems less common now. These days, you hear more the idea that the only thing that’s out there is a kind of life force that is nice and encouraging and, if you like (and perhaps if you learn some techniques), can be harnessed for your own benefit. This is not the God to whom all hearts are open and from whom no secrets are hid because he knows us better than we know ourselves. This is not the God whose healing, rescuing love has intervened in history over and over in ways so inventive even the finest intellects struggle to describe them. This is not the God who is passionately concerned about the hungry and the outcast and the prisoner. This is not the God whose mercies are without number and whose piercing insight into the human condition regularly takes our breath away. This is something more like electricity. It’s not personal, it doesn’t take initiative, but it’s generally benevolent, and if we draw on it in times of need it helps us feel better about ourselves and be good people in general. That version of God, rooted in what sociologists of religion have been calling Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, isn’t unrelatable or sinister; it’s just terribly boring. It’s banal. It’s beneath us. If that were what Christians meant by the word God, again, I completely understand people feeling that their time could be put to much better use than by getting involved in church. If you were attempting to come up with an idea of God, and what you came up with were either the newer Moralistic Therapeutic Deism idea or the older powerful man on a throne idea, then naturally you would see the Trinity as an optional layer of icing on top of it. But in the Christian way of thought, there’s nothing more basic than the Trinity. We don't add that concept on top of a more general concept of God; we start there. We start with the Trinity, because it’s who God is, it’s what Being is, it’s how the universe works. The heart of reality is given its shape by this three-personed God, constantly giving and receiving love from Father to Son to Spirit and back. All human fulfillment, as well, is given its shape by God being like this: Three persons made who they are by their relationship one to another. It is very different to speak of a monarch or a force than it is to speak of a God who is actually relational in his essence and to whom loving and being loved are so central that they make him who he is. The New Testament claims, after all, not that God can be called "loving," but that God is love. He is love. So if we trace every experience of love in human life back to its origin with the help of what God has revealed to us in Christ, we come again and again to this living community of self-giving at the heart of the Trinity. Every experience of beauty leads the same place. Every experience of justice. Every experience of mercy: Trace it back. Trace it all the way back and you come to the moment at which the possibility of our ever experiencing love and beauty and justice and mercy in the first place was birthed out of the loving, beautiful, just, and merciful community of the Three in One. See, what people tend to come up on our own is nearly always some version of a God that is less than us. An isolated monarch whom we can’t really open up to and who might be about to turn oppressive at any moment, or a force we can harness and take advantage of for our own ends. (And there are other possibilities than just those two, of course.) But what Christians refer to by the word God, the God who took the initiative to reveal himself to us in Jesus Christ, is so much more than we could ever have come up with. A community of love who is so radiant and outgoing that he overflows into creation. Different, yet united. Just, yet merciful. Endlessly fruitful, endlessly generous, endlessly deep, and holy, holy, holy. A God we can want, and love, and learn from, and drink of, and marvel at, and adore with every fiber of our being forever. Starting now. Let us pray: Almighty God, you have revealed to your Church your eternal Being of glorious majesty and perfect love as one God in Trinity of Persons: Give us grace to continue steadfast in the confession of this faith, and constant in our worship of you, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; for you live and reign, one God, now and for ever. Amen. The image with this post is William Blake’s ‘Sketch of the Trinity’. God the Father, embraced under the wings of the dove-like Holy Ghost, receives and returns the embrace of God the Son.

1 Comment

Chris Eliason

6/7/2016 11:45:53 am

Someone very close to me does not believe in God and this sermon has helped me to understand this.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed