A sermon preached by the Rev. Beth Maynard on the First Sunday in Lent The Gospel of Mark’s story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness is extremely brief: so brief, in fact, that in order for today’s reading not to just be comically short, the lectionary fills that story in with a few verses before and a few verses after. As Deacon Chris read it, I’m sure some of you thought, “Wait, Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan…. – didn’t we just hear that at the Baptism of Christ? And: Jesus came to Galilee, saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news’ – didn’t we just hear that on Annual Meeting Sunday?” Well, yes and yes. But what we didn’t hear yet was what happened in between. “The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. He was in the wilderness forty days, tempted by Satan; and he was with the wild beasts; and the angels waited on him.” I’d like us to just take some time this morning to study what happened in between. The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. The Spirit has just descended on Jesus at his Baptism, and the very first thing he does is to drive Jesus out. When you compare that language to some of the tame and sentimental images of the Holy Spirit we encounter, it kind of gives you pause, doesn’t it? The Spirit drove him out; there’s a violence to it, an impulsion; a sense that Jesus barely has a choice, the action of God is so forceful. This next step in Jesus’ vocation is important business and the Spirit is going to get it done. So where does the Spirit drive him? Out into the wilderness. Now if you are familiar with the Bible you know that important stuff happens in the wilderness. It’s where Moses met and argued with God before he was changed into a great leader of Israel. It’s where the Israelites journeyed and grumbled for 40 years before they entered the Promised Land. It’s where the prophets, centuries later after the congregation had become corrupt and apathetic, promised that God would make straight a highway for himself to re-encounter his people. ...

0 Comments

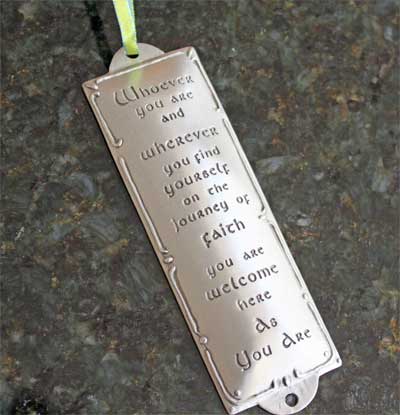

A sermon preached by the Rev. Beth Maynard Every time you walk into this worship space, there is a small metal plaque that greets you, just at eye level. It’s not ostentatious, but it’s there on every door. I wonder if you have noticed it? Here is what it says: Whoever you are and wherever you find yourself on the journey of faith, you are welcome here as you are. Lori told me this week that we still have some for sale in the Bookstall, so if you like that saying as much as I do, you know where to get one. Over the years, I have had, many times, the experience of someone coming to see me, sharing something about themselves – maybe their current feelings about God, their life situation, their history – and asking “Can someone like me come to this church?” I don’t believe I have ever said anything but “Of course you can,” and I’m grateful to be in a denomination that, at least at our best, espouses the message of that plaque: Whoever you are and wherever you find yourself on the journey of faith, you are welcome here as you are. I’m a realist, though, and I think that over the years, every time I’ve assured someone that yes, a person like them is welcome, I’ve also cautioned them that I can’t guarantee that every single Episcopalian they meet will treat them with consistent unconditional love. There is, after all, a difference between espousing a high-level theory of loving your neighbor and actually doing it on the ground. In his book People of the Way, Fr. Dwight Zscheile tells the story of his family attending Mass at an Episcopal church with a banner out front proclaiming that the parish offered “RADICAL HOSPITALITY!” However, not a single person spoke to them, and the minute his three-year-old rustled a piece of paper during the liturgy, he found out from a series of hostile glares how extremely limited their actual ability to practice actual hospitality to actual human beings was. It’s interesting in today’s Gospel to think about how hospitality functions and how it doesn’t. The text tells us that Jesus and his disciples went to Peter’s house after synagogue one day. But Peter’s mother in law was sick when Jesus arrived, so instead of her welcoming and reaching out to him, he reached out to her. However, when she discovered he’d made her well, she got up and served a meal after all. It’s all a bit topsy turvy. We have welcoming in which the guest takes care of the host, and then the host welcomes the guest.

But it gets even more topsy turvy, because a horde of local residents show up. Are they coming because they’ve heard Peter’s house is welcoming? No, they’re coming because they’ve heard that Jesus can help them. He has brought the Kingdom in person, he can heal and save, and there’s not a family on earth, now or then, that doesn’t need what he has. So they come from all over, streaming to this little house, lining up to come face to face with God incarnate and receive from him in person. Mark says, “The whole city was gathered around the door.” Hours and hours of specific manifestations of the Kingdom later, Jesus goes away by himself to pray. When Peter and the others finally find him out in the middle of nowhere, they’re flushed with triumph. “Everyone’s looking for you!” they announce. They have made a splash, they’re perfectly positioned to trade on the credibility they’ve generated, put a banner out front of Peter’s house, and have people come join up. But Jesus resists. He says the most extraordinary thing. He says, “Let us go on to the neighboring towns, so that I may proclaim the message there also; for that is what I came out to do.” His priority isn’t to build something where he’s doing well and get people to join it, but to go out offering the experience of the Kingdom. What he came out to do wasn’t to attract people to a gathering place, but to go give away what God is doing in and through him. To give away transformation, reconciliation, abundant life. I expect Peter and the others were baffled at this strategy. I know we contemporary Christians usually are. It would be so much easier if Jesus had come to attract people to a gathering place. Then his followers could just gather. And then we could just welcome anyone else who wanted to gather with us, and we’d be all set. That’s not hard to do. It happens everywhere: Milo’s restaurant does it, the YMCA does it, the Krannert Center does it, book clubs do it; it’s common in our society to experience places that make people of all kinds who come there feel welcome. But Jesus didn’t prioritize that; it was a byproduct of what he prioritized. What he came out to do was to give away what God was doing in and through him. To announce the Kingdom and demonstrate it. And everyone needs that; it crosses all dividing lines. Paul says the same thing in today’s Epistle. Rich, poor, weak, strong, Jew, Gentile, law-abiding or lawless: all those differences were swept away by the compelling central concern of giving away what Jesus offers. Something you can’t get anywhere else. Things that come as byproducts of it may be available elsewhere, but what he came out to do is only available in him. You can get welcome qua welcome lots of places. In fact, you can get many excellent byproducts lots of places. Friendships and art and music; chances to serve at something you find meaningful, thoughtful conversations; coffee, fun social gatherings; support when you’re down, personal growth -- all byproducts, things that come along with the real focus of giving away what Jesus offers. And this sort of takes us back, I think, to that beautiful plaque. Whoever you are and wherever you find yourself on the journey of faith, you are welcome here as you are. Actually putting that theory into practice, to me, is part of Anglicanism at its best, but putting it into practice gets easier the less you deal in byproducts. Episcopal churches that can proudly point to their deep diversity -- and they’re rare – churches where all kinds of households, all age groups, all ethnicities, all economic and educational levels are truly involved: those are inevitably the churches that have found ways to let byproducts be byproducts and focus on the central mission. There’s an anthropologist, Paul Hiebert, who analyzes churches as either bounded sets or centered sets. A bounded set is a group of people defined by a boundary along the edges that separates those who are inside from those who are out. Most human groups are bounded sets. Think of a horse corral. The horses are all inside the same fence; if they’re inside they get fed and cared for, and any outside horses have to be tamed first and accept the norms of life inside. Churches that function like this always treat some byproduct as the fence. It might be a doctrine they promote, it might be a behavior they expect, it might be a matter of taste. Or the fence can even just be “we need a lot of time to get to know you and be convinced you fit in with us.” That’s a bounded set. The other model this anthropologist describes is a centered set. In a centered set, there is no fence defining “us” over against “them.” The set gets its identity not from a boundary you have to get past to belong, but from what is at the center. There is something so compelling at the center of this kind of collection of people that it is what defines and connects them. So involvement is not based on needing to become “one of us” before you can belong. The key question is not whether I am in or out, but how am I relating to the center? People are free to be who they are, standing at different places, moving towards the center at their own pace. Those who are drawn most powerfully by the center will probably be fairly involved with each other too, but that’s a byproduct. All kinds of people will be in the gathering because all kinds of people find the center magnetic, but that’s a byproduct. If a horse corral pictures a bounded set, a centered set is more like a water hole in the African grasslands. Animals that live in the area are naturally drawn to the water. In the dry season, it’s not uncommon to find animals that at any other time of year might stay away from each other, all peacefully sharing that one water hole, not because of some campaign about how gazelles need to be more accepting of springboks, but because there is water in the water hole. When churches exist as centered sets rather than as boundaried gatherings trying to attract people to get past their fence, when churches let the magnetic power of what Christ offers be their center rather than define boundaries by byproducts, the same kind of thing happens. People of all backgrounds and beliefs are welcomed to join the conversation, to be deployed in service, to learn from and challenge each other, and to encourage one another to move ever closer to the center. Because we are all drawn to the same well, all thirsty to drink from the same source of the same living water. Because Jesus is that magnetic and what he offers every person is that important. Because this, as he said to Peter this morning, this is what he came out to do.  A sermon preached by Deacon Hopkins on Sunday, February 1, 2015 “Knowledge puffs up, but love builds up.” If anyone had ever told me that I would be preaching on a lesson about sacrifices offered to idols, I would have thought they were talking about someone else! But here I am getting ready to do just that. Sometimes the Holy Spirit does do unexpected things and this morning, the epistle is the lesson that has spoken to me. Paul’s letters were generally written to address concrete situations that had occurred in the Christian communities that he had established. The issue in this morning’s passage is seemingly irrelevant to us who live in the western world in the 21st century. Food that has been sacrificed to idols does not play an important part in our day-to-day life. But I think we can learn from this long ago situation in Corinth and Paul’s approach to the argument that those early followers of Christ were having. First some background. Corinth was a cosmopolitan place in the mid first century Roman Empire. It was a busy hub of eastern and western trade and the center of Roman culture in Greece at the time. There was a mix of people living there who followed very different religious traditions. There was also disparity in economic situations; some were very wealthy and others were so poor that having enough to eat regularly was a problem. Some were very well-learned and others had little to no education. There was a wide range of people on many fronts. For the well-educated and well-to-do, there was an active social scene. There were many lavish parties with excesses of food and drink. It was a city with lots going on. Corinth was one of the very first places that Paul brought the message of Christ. He lived there for about a year and a half establishing house churches which regularly came together to share the Lord’s Supper. When Paul moved on to bring the good news of Christ to other places, the new community of believers in Corinth continued to grow. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed