At the risk of pointing out what is by now a tired cliche, we’re suffering from shorter and shorter attention spans these days. Everything is so immediate, so accessible, that there is little reason to sit with and work through the slow and the mundane. And so our fleeting attentions go hand in hand with our demand for instant gratification, which not only grows stronger, but there’s always more efficient means of satisfying that demand. We don’t even have to wait for the technology that takes the waiting out of life. Now, lest you think that I’m just wringing my hands about all this, I also believe that it’s not totally our fault. It’s not just our own impulsive lack of discipline that accounts for this state of affairs. In fact, part of the reason we’ve lost the strength of our attentions is that our world is intentionally filled with things that are not worth paying attention to. Everything is convenient for the purpose of being disposable; it’s not supposed to be lingered upon, contemplated, or saved. Our inevitable discontent with this disposable world can thus be manufactured that much more effectively, and there’s a lot of money to be made off of our discontent. Anyway, for me, living in a world like this means that I want things to be entirely straightforward and accessible up front. I want to immediately understand the whole of something before I devote my time and effort to it. Because I only have so much time and effort, of course. So when I’m reading an article online, to use a common example, I’ll often impatiently skim through the body of the text to the conclusion. Then, if the conclusion suggests something worthwhile, I’ll maybe go back and give it my proper attention. Maybe. But the point of this exercise is to actively avoid humbling myself to join the writer in the gradual development of his or her thought or argument. Because to do that would be to risk sacrificing the detached and disinterested position I occupy as a consumer, hovering over things instead of committing to them. After all, I might even be changed -- or, God forbid, transformed -- if I risk that commitment. And this risk goes right in the face of the dominant logic of modern life. We are conditioned in this society to demand the whole of something up front, immediately, so that what is relative and conditional is our commitment to it. In short, we insist on maintaining our control over what we give ourselves to and over the extent to which we give ourselves. This perspective on life is the exact reverse of what we find in Jesus’ various parables about the Kingdom in today’s Gospel. There, we find that what is relative and conditional is not our commitment, but the Kingdom itself; it is like the mustard seed that slowly grows from being the smallest of the seeds into a mighty tree which provides shelter to the birds of the earth; it is the yeast which is so incorporated into the flour that it becomes impossible to differentiate one from the other, even as it as irrevocably transforms it. So while we’re accustomed to expecting fixed and definite objects for our own measured commitment, the Kingdom itself is what is measured. Moving on, Jesus says that the Kingdom is also “like treasure hidden in a field, which someone found and hid; then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field.” It’s “like a merchant in search of fine pearls,” who, “on finding one pearl of great value... went and sold all that he had and bought it.” Again, our normal ways of engaging the world are being challenged. Not only is the Kingdom like something that roots itself within the processes of our world, thereby being difficult to comprehend in full, it nevertheless demands a full and unyielding commitment on our part. Our commitment to the Kingdom is to be decisive, total, just like the one who finds the treasure or the merchant in search of the greatest pearl. And when you combine these analogies from Jesus, that we are to go all in on what can actually be difficult to discern, we are faced with the risk and the adventure of faith. Returning to the analogy of the mustard seed, whenever I have heard this parable in the past, my mind has often pictured a tiny seed that automatically turns into a giant tree without much attention to what it is that is actually be described. Trees take forever to grow. Not only that, but they even remain latent and hidden in the ground as seeds for a time before they germinate. And then they’re just saplings. But Jesus says that the Kingdom is like this, which means that it’s not only like the final maturity of a tree whose branches provide shelter, but also like every stage of the tree’s growth. The Kingdom is like the seed, the sapling, and the mighty tree. This is why we are to always be on the lookout for those “foretastes of the Kingdom” that Mother Beth talked about last week, fully investing ourselves in those small little glimmers of redemption. In fact, the Christian life is this present age is nothing other than our participation in those foretastes. So that, I think, is the take-away from the first few parables that Jesus tells us today. We never know at what stage of development we might encounter an outpost of the Kingdom. It might be a hundred years of prayer and devotion saturating the very bones of a place, like here in this sanctuary of Emmanuel. How leavened must the flour of this community be with such longevity? Or, it might be a sudden sprouting of the most fragile and delicate possibility of redemption in your life or the life of a loved one. But once we discern it, we are called to suspend all manner of shrewd calculation or keeping ourselves at a safe distance “to see how things pan out.” No, we’re to go all in for the life of the world as is found in those foretastes, just like the merchant who sells all he has to purchase the pearl of great price. After this, Jesus moves to a different image of the Kingdom, that of the “net that was thrown into the sea and caught fish of every kind.” Jesus continues that: ...when it was full, they drew it ashore, sat down, and put the good into baskets but threw out the bad. So it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come out and separate the evil from the righteous and throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Not exactly as stirring of an image as the others that I’ve described already, but it’s no less important for a grasp of the nature of the Kingdom of Heaven. It teaches us that the Kingdom is not necessarily found to be this discreet and clear-cut phenomenon. It’s not necessarily something that we can clearly distinguish from something else. Because like Jesus says, the net of the Kingdom pulls in fish of every kind, both good and bad, and until the fishermen sort out the fish, the net is just one big mixed bag. And it’s not for us to do the sorting. This means that on this side of the final judgment, the Kingdom is never to be found in a totally pure or final state. For the time being, the Kingdom contains within itself the brokenness of the sinful world, even as it also contains the goodness of the saints. And just as a net full of fish convulses and squirms with the frantic movements of a thousand little fishes, so too does this present life in the Kingdom. We are joined together in solidarity with both the good and the bad -- we’re all in this net together -- and somehow, this too is the Kingdom that we are to drop everything for. It’s complicated, this Christian life. Here toward the end, I want to close with some thoughts about some habits and practices that might aid us in discerning this mysterious Kingdom. Recall that our world today is one which actively trains us in patterns of living which make this discernment more difficult than it already is. Consumerism, after all, is nothing other than the failure of proper attention, an habituated distractedness which is designed to keep our affections suspended from ever making any real commitments. So cultivating periods of single-mindedness, through prayer, silence, and solitude, can help overcome these vices. They help tune our gaze to the things above, the mysterious things of the Kingdom that we might not otherwise see. This is the point of fasting as well, as the lack that it creates becomes the very space in which contemplation can advance. You might find the treasure that had been hidden. In short, unite yourself with the experiences of your day; don’t just pass through them as through the aisles of a supermarket, suspended in detachment. All in all, remember that the Spirit blows where it chooses, and it takes the Kingdom with it, in and through all the corners of this material life. It rests for awhile where you’d least expect it, perhaps even suffering there by virtue of its faithful presence in a place that despises it. That’s why the Kingdom is the Gospel, for just as our Lord on the cross was flanked on one side by one who taunted him, and on the other by one who wished to join him in paradise, so too are we, as citizens of the Kingdom, surrounded at times by those who afflict us and by those who, like the birds who rest in the branches of the mustard tree, come within our fold for a relief that is found nowhere else. Amen.

0 Comments

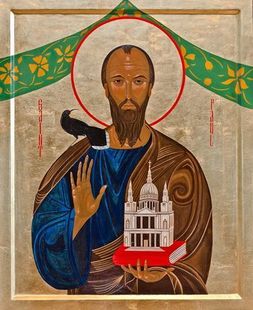

July 23, 2017 The Rev. Beth Maynard We’ve been using Romans for our Epistle all summer, so week by week we’ve heard Paul explaining sin and law and grace. And last week we moved into the emotional climax of that teaching, where we get three weeks reading Romans chapter 8, one of the greatest passages in the New Testament. So as far as our Epistle goes, we’re in the middle of a sort of three-week party, where Paul is celebrating all that is ours once we have been redeemed by Jesus Christ. Redemption is a big word, and Paul is a big thinker, and he lays out a big picture of what this means. And this morning I want for us to try to widen our vision out and think as big as Paul does. Let’s start that widening by asking how two pieces of this reading fit together: you might have noticed, about four lines down, that Paul celebrates that if we are redeemed people, we are already children of God. He writes, “You have received the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry, "Abba! Father!" In that verse, our adoption is a done deal. Yet skip just a few lines further down; he’s still talking about our adoption by God, but here it lies in the future: “We groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as children, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we were saved.” How do those two things fit together? Are we already redeemed and adopted, or are we waiting eagerly for it in hope? Paul’s answer, and the New Testament’s answer, is both. The Feast of St. Mary Magdalene

Fr. Mac Stewart The ark of the covenant must have been a marvelous sight to behold. Acacia wood overlayed with pure gold within and without; on its four feet, four rings of gold to hold the poles of gold by which the ark would be carried; on its cover, a mercy seat of pure gold, flanked on either side by two golden cherubim, their faces turned to one another and their wings spread wide to overshadow the empty mercy seat between them. A marvelous sight to behold…but one that was rarely in fact beheld, seen only by the high priest only once a year, and that only after he had covered it in clouds of incense. This was, after all, the place where the LORD God of Israel, the one on whom no one could look and live, had promised to meet and speak with his people, between those two glittering cherubim above the empty mercy seat, in the Holy of Holies. We’re gathered together today as the Body of Christ to ordain and set apart for the priestly ministry of Christ’s holy catholic Church Caleb Scott Roberts. The ministry to which you’re called today, Caleb, is not unlike the ministry of the priests of old who carried the Ark of the Covenant in the midst of the people of God as they made their pilgrimage through 40 years in the wilderness. You are now to be a steward of the holiest things in the world, the Word and Sacraments of the gospel of Jesus Christ, for a holy people wandering through the wilderness of this world. The chalice and Bible that Bishop Dan is about to hand you are signs of your stewardship, of the hot and holy things that you will preach with your lips and hold in your hands, as dangerous and explosively potent as the Ark itself. You will bear in your hands and on your lips the ministry of reconciliation, the power that has been unleashed in the world by Jesus Christ, the very power that made all things and is now making them all new, bringing peace with God, neighbor, and self by the blood of Christ’s cross. And you will be called upon to wield this power for your people both in the daily and weekly round of ordinary Christian life, and in the most extra-ordinary and intense experiences they’ll ever face: preparing them for baptism, confirmation, and marriage; counseling them through the paralyzing moral dilemma, the persistent sin; praying for them as they walk through the bitter familial battle, the trials of a wayward child, the devastating illness, the untimely death. Would you rather wear a yoke, or carry a burden? You probably have no immediate answer to that dilemma, but the way those two images are framed for us today in the Gospel of Matthew may make it a little easier at least to understand the question, from a Christian point of view. At the end of today’s Gospel reading, Jesus utters a verse that anyone who prays Compline out of our Prayer Book knows. “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.”

This is an interesting image, and I can see why the church has installed it at Compline, the bedtime office. If we have taken Christ’s yoke, we often do need a reminder that he has already taken responsibility for all that we are carrying around with us. And when you open your Prayer Book and read that verse before bed, there is a sense of letting everything go into the arms of God. You may even find that making that act of trust each night means you sleep better. I recommend it, just as I recommend all the other aspects of the Prayer Book system. Page 127, before bed. Give it a try.  Good morning. My name is Caleb Roberts and I’m the brand new curate here at Emmanuel Memorial. Our short time here so far has been joyous and it’s been in no small part due to the overwhelming generosity and hospitality of your welcome of myself, my wife Julie, and our kids, Alice and Charles. I want to again thank you all specifically for the bounty of the pounding on our first Sunday here. We’ve put it all to good use and it’s made for a lovely little Y2K bunker down in the basement. In any case, I am delighted to be with you all this morning for this first opportunity to preach to you all today. It’s not generally common for Episcopal preachers to take up the Epistle appointed for the given Sunday as the text for their sermon, and there’s a good reason for this; it is, after all, in the Gospels that we are most immediately faced with the account of the life, death, and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ that so inspires our devotion towards him. But when we come across a passage such as today’s portion from St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, we are confronted by the bold exploration into the mystery of grace that only Paul can give us. Of all the truths of the Christian faith, the one that intrigues me again and again is its embrace of the body. Ours is a material religion, rooted not in some spiritual escape from the limitations of embodiment or the physical world, but rather in the midst of those particularities. Being in Christ is about being fully, authentically human, which means that grace works in and through our bodies. As Paul puts it, we are to present our bodies as instruments of righteousness by the grace and power of God. You’ve no doubt heard someone describe him or herself as a “creature of habit,” but the reality is that each and everyone of us is a creature of habit simply by virtue of being human. In order to survive in a world of things, we create patterns in our lives so that we can order ourselves towards continued life on earth. These patterns are our habits, the routine actions by which we direct ourselves towards the goal of life. And herein lies the challenge of being human, because it’s not a given that we always pattern our lives to achieve life. We’re not mere creatures of instinct, we have free will which opens up the possibility that we can actually habituate ourselves towards self-destruction. So consider a bad habit in particular, because if you’re like me, those are the habits that I’m most conscious of. There’s actually a good deal of paradox involved with a bad habit. On the one hand, it feels like a negative imposition on your daily life; in your mind, you know that it doesn’t make your life better and that it might actually be a real obstacle to living life to the fullest. You experience your bad habit as a sort of bondage; you’re enslaved to it, in a way. And yet, is it not also true that to let yourself fully succumb to it yields a certain sense of freedom? You certainly get to stop worrying about it for the time being, and to accept your bad habit feels like allowing yourself to do what you want. On the other hand, to do the work of overcoming the habit is hard, and it might be more uncomfortable than just persisting in the bad habit. Beating the habit leads you into another kind of bondage; you’re now bound to the new life of consciously maintaining your freedom from what has passed away. This new life is defined by new habits which replace the old, and the so-called “freedom” you once had to pursue your bad habit now appears to be a pale comparison to the real thing you’ve now achieved. You trade the false freedom that came with your bad habit for the true freedom that comes with good habits. This is what Paul is getting at with his metaphor of slavery, slavery to sin or slavery to righteousness. And just to make it clear, as Paul himself does in our epistle today, the “slavery” being discussed here is merely a “human term” employed for the sake of our understanding. By using slavery as a metaphor for human life, we are in no way underwriting or validating the abomination of slavery as we know it from the American story. Rather, his point is to show that we are inescapably ordered by something external to us, some transcendent principle which is beyond our grasp. We are not neutral, as nothing in Creation is. We live, therefore, in the midst of a complex network of habits and desires, and somehow, we are tasked with navigating this network for our whole lives. Sin enters this network when we redirect the desire that only God can fulfill towards some lesser thing. It’s what happens when we seek a counterfeit form of transcendence by exploiting the things around us. And these sinful acts accrue together to form what Paul calls the “body of sin,” which is not only the individual self that is fully habituated towards sin, but I’d say it’s also the entire corporate body of the human race, all of us together building up systemic structures of violence and oppression. The body of sin includes the powers and principalities. In any case, this is the slavery to sin that human life has come to be defined by. We have the habit of exploiting ourselves and others to achieve a false sense of freedom which leads only to death. And when grace comes into the picture, these habits of sin are revealed to be the tyrants they really are. Grace overthrows them and places us back into right relation and service to God. For sin no longer has dominion over us. And now we are able to present ourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life. In this new life of grace that we enter into by the waters of baptism, obeying the demands of righteousness can now be an act of freedom, and therefore of love. The fear of the law which once compelled our obedience has been cast out by the love of the Son for the Father in which we now participate by faith. His love is now our love. And as slaves to righteousness, the only dominion that sin can wield over us is the dominion we choose to create again in ourselves. This is why Paul is so insistent that the gift of grace is by no means a cause to sin that grace may abound all the more. Sin only functions as a rival master; and so our willful obedience to it can only result in another slavery. But what has been taken away by the work of Christ is the absolute bondage of that slavery to sin. We can now resist it, resting in the true freedom of union with Christ. So whereas we were once slaves to sin, our wills being bound to obey the demands of iniquity unto death, we now have died to death in Christ, and thus we are now slaves of righteousness, free to willingly obey the demands of justice. So as you go about your life with Christ, saying your prayers, sharing in the sacramental life of the Church, giving alms to the poor, rest in the knowledge that it is none other than the grace and power of Christ which guides you along. For you are bound to him in his death and resurrection -- and thus bound to his Gospel -- so that you can present your bodies to God as instruments of righteousness. So thanks be to God that you, having once been slaves of sin, have become obedient from the heart to the form of teaching to which you were entrusted, and that you, having been set free from sin, have become slaves of righteousness. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed