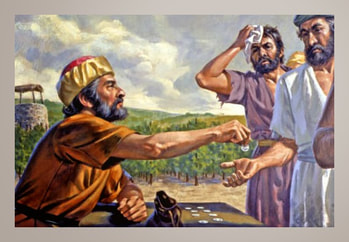

By now, you may have noticed a recurring theme that has been developing as we have been making our way through Matthew’s Gospel: that the Kingdom of God resists all forms of human calculation. Three weeks ago, we heard the well-known paradox from Jesus that “those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.” Here, what normally strikes us as an unremarkable bit of common sense -- self-preservation, that is -- is associated with kind of spiritual death. In the next week’s gospel, the disciples are told that “whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” We learned there that the work of the Church is never merely a matter of human administration; heaven itself is determined somehow by the activity of the Church, binding and loosing. Which in the end means that the Church should go about its business in a radically different way than would otherwise be expected. The knowledge that what is bound and loosed on earth determines what is bound and loosed in heaven itself determines in turn what we bind and loose on earth. And last week, Mother Beth took us through the parable of the slave who, though he was forgiven an unfathomable debt by his master, nevertheless immediately went a demanded a much smaller debt from one of his debtors. As Mother Beth pointed out, the slave couldn’t comprehend that the master’s gesture suspended the whole relationship of debtor-creditor, and that having been liberated from that relationship, he was then expected to take that liberation into his own relationships. What he should have realized was that the grace of God disrupts the categories of deserving and undeserving altogether. This week’s gospel continues this theme with another parable of Jesus, this time about a group of workers in a vineyard. Though I’ll eventually offer a different angle on this parable, the standard interpretation is powerful as well, and warrants a brief discussion. According to the dominant reading of this parable, what we see here is an account of God’s historical plan of salvation that begins with God’s ancient covenant with the Israelites and culminates with the inclusion of the Gentiles into the people of God. The tension between the workers who started their work at the very beginning of the day and those who only came in at the last hour recalls the understandable resistance of the Jews to the newcomers. Did not the Jews bear the burden of the day and the scorching heat? Did they not undergo slavery and exile over centuries while holding on to the promises of God for dear life? What a scandal it is, then, to countenance the equal pay and standing of those who barely broke a sweat. Of course, Jesus, assuming the voice of the landowner, explains away the scandal clearly enough. After some of those who had worked all day begin to grumble, with one of them coming forward to register their grievance, the landowner replies:

‘Friend, I am doing you no wrong; did you not agree with me for the usual daily wage? Take what belongs to you and go; I choose to give to this last the same as I give to you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?’ So the last will be first, and the first will be last.” In other words, the landowner reminds the offended workers that it was a false assumption on their part that they would somehow receive more than the day’s wages which they agreed to, simply because those who came later in the day received the full day’s wages as well. And I wonder if revealing this false assumption was the point of paying the last workers first, maybe of the whole “first shall be last and last shall be first” paradigm. Perhaps it was to emphasize the total prerogative of the landowner with regard to the wages. Those workers who came late in the day are paid first so as to show those who had worked all day long something about the nature of the wage itself. And what is it that we, with those first workers, discover? It caught my attention at the very beginning of the passage that the landowner “went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard.” This means that the laborers weren’t already employed by him. Were it not for the landowner’s recruitment, it stands to reason that even the first batch of workers who began working at the crack of dawn would have been just as idle as the rest of the workers to come later in the day. And to repeat it again, it is the landowner who actively goes out in search of workers to employ; it is on account of the landowner’s initiative that any of the workers are employed and then paid at all. But as anyone who has worked in manual labor will tell you, the days are long, and by 3:00 in the afternoon, it appears that the initial group of workers have forgotten the utter contingency of their employment. Rather than remembering that it was only because the landowner sought them out that they are working for a wage in the first place, they subtly establish themselves as the measure of what would constitute just payment. As new workers arrive at 9:00, noon, 3:00, and even 5:00 in the evening, the first workers imagine that these other workers’ pay will be calculated in proportion to their hours, not the landowner’s discretion. The point that Jesus is making to his fellow Jews, therefore, is that they, like the Gentiles, all started in the same condition. All humanity was wandering aimlessly, all were standing idle because no one had hired them. And because the landowner represents God himself, the inherent grace of the act whereby God seeks us out and employs us as his workers transcends all attempts at quantifying it among people. The Jews, figuratively the first workers to be called, ultimately share in the same gracious approach of the landowner that the Gentiles do, the Gentiles being those who were hired at 5:00. But there’s more to this parable than just disrupting our ideas about priority and fairness. Because even though the parable makes sense, you’re not alone if you still think there’s some dissonance between the metaphor of wages and the reality of grace that it’s supposed to stand for. The point of the parable may be that the grace of God is not quantifiable according to human standards of priority, of who comes first and who comes last, but the very metaphor chosen to reveal this truth is quantifiable by definition. We’re all acquainted with wages and we all intuitively understand how they work, the audience of this parable included. And so we can concede the argument to the landowner that justice was not violated in paying the last workers the same wages as the first workers, so long as the first workers received what they had agreed to. But the landowner is clearly operating with a different logic altogether when it comes time to pay the workers. The landowner meets the demands of justice, but goes beyond them into the realm of pure generosity. This leads to the other angle on this parable that I want to think through today. I want us to think of the various groups of workers as different stages of activity in a single person’s life. Imagine yourself and your own life as representing the entire work day in the parable. It’s probably because of where my mind has been lately that when I read that the landowner went out in search for workers at 9:00, noon, and 3:00, I immediately thought of the monastic hours of prayer. I just acquired a copy of The Anglican Breviary, an old-fashioned book of offices adapted for Anglican use in the early 20th century, and have been trying to wrap my head around it. So, that explains that. Nine, noon, and three were hours that monks would have stopped everything and said the appropriate office of prayer. But I’m no monk. As I read of each group of workers being approached at those different hours, being found standing idle by the landowner, I realized how familiar that sounds in my own life. How many days do I find myself at nine, noon, and three standing around spiritually idle, imagining that no one has hired me? Spiritually unemployed, so to speak. And even when I do find some good work to apply myself to, briefly energized with purpose and intention, there’s often a kind of despair at having begun work so late in the day. I can’t help but think of all the time wasted beforehand. Of how I’m not a real worker, because real workers dutifully start at sunrise and put in a full day’s work for the landowner. It’s embarrassing to arrive at 3:00 in the afternoon as those who are caked in dirt and sweat look up from their toil upon me in a sort of distanced pity. Or so I think to myself. Surely the little hour or two of work I’ll put in for the Lord on this vineyard will just be counted as much. I’ll get paid accordingly, for these two little token hours of work -- how would I dare think that my small labors would warrant anything more? It’s my own fault, after all, and I should stop hitting the snooze button so as to be ready to join the diligent at the first hour. Maybe you’re like me. Maybe you think that you’re always behind, always trying to catch up on your spiritual life, feeling idle, having missed the landowner’s first recruitment. But what happens at the end of the day for those like us? The landowner calls us up first and pays us the full measure of the day’s wages. You are not a temp, says the landowner. You are not unofficial, illegitimate, invalid, provisional. You’re mine, says the landowner. You answered my call and set out to do the work that I have prepared for you to walk in. And no matter how much endurance those around you may have, no matter how many feats they have accomplished, it is only the infinite grace which I bestow which they have received. And being infinite, it is not subject to calculation or accounting. All my workers share in the same generosity which drove me out in search for you. We can never receive more than the grace of God and we can never receive less. Five o’clock in the evening is therefore the perfect time to return to the vineyard if you’ve found yourself idle. That the landowner goes out again and again throughout the day suggests that the call to work is unremitting; it’s always there should we open ourselves to hear it. And the wages that wait for us there are the same as they always are. The sufficiency of grace is nothing other than its abundance. Such is the Kingdom of Heaven.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed