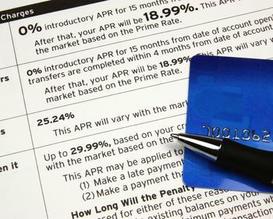

Each year, millions of credit card solicitations are sent out in the U.S. You’ve received many, I’m sure. Congratulations! you have been preapproved, they say, for a credit line of $25,000. If you act now, you can get triple airline miles and transfer all the balances from your other cards at a low introductory rate, plus pay off your student loan with one of our personal superchecks. Only if you read the fine print do you notice that those are charged as cash advances, which carry a 29% interest rate from the day they're withdrawn, and that low introductory rate is good for just the first quarter. But hey, the minimum payment is only $30. It would be awfully easy to run up a pretty hefty debt that way. Keep your cards at the limit, sign up for every new one, keep juggling balances from one account to another, and when you get stuck, pay it off with a cash advance from a different card. The slave in today's parable had dug himself into just that kind of hole. Jesus tells us about the debt he had run up with a figure so outlandish that he is clearly going for a laugh. Ten thousand talents, Jesus says; well, one talent was about 15 years' wages. The slave owed his king what he’d have earned over a period of 150,000 years. Let's say his credit cards were maxxed out at, oh, ten billion dollars, and we'll get about the comic effect Jesus wants. Hard to pay that off at $30 a month. hen the king calls him in to settle his account, you can just hear the ominous debtors-prison-type music rising in the background. The king confronts the slave with just how far in the hole he has gotten, how ludicrously unpayable his debt is. And then the terrible verdict: he and his family are to be sold, everything he owns repossessed. The slave begins to beg for mercy. But listen to what he says. Not "please help me, I'm in way over my head." No, he makes the absurd claim that if the King will simply give him a little more time, he will pay every penny. The slave never admits he needs help. All he asks is that somebody stall the collection agency. He has actually talked himself into believing that it'll work to spend the rest of his life pathetically chipping away at this ten billion dollar debt, one minimum payment after another.

Now, Jesus hopes we will see that this reaction is ridiculous -- which it is, but it's not uncommon. Not in the context of the reality of human nature. Pastoral counselor David Seamands, whom I want to borrow from as we talk about our parable this morning, has pointed out that we human beings function within a debt-based system. We all have a built-in debt collector inside. You know exactly what its voice sounds like, if you'll think about it. "She owes me an apology." "He won’t get away with this if I have anything to say about it." "I've put in my time; the other people ought to do a little work for once." It's interesting: the word "owe" and the word "ought" come from the same root in English. Owe and ought. That makes sense, because they both function in the debt system. See, sometimes the interior debt collector wants you to collect from someone you think owes you, but often it’s also trying to collect from you. When you feel as if you have failed to measure up, then it says things like "You ought to have done better at that." "Your grades ought to be higher than B's." "You ought to have had a promotion by now." Wherever this cycle begins -- and I've never met anyone who can remember that far back, because in a fallen world we're all in it from the moment we're born -- wherever this cycle begins, it is self-perpetuating. The score-keeping. The resentment. The striving to pay your own way, to deserve things, along with evaluating others as people who are either deserving or undeserving. The slave in this story is trapped in that score-keeping cycle, and he turns to the only solution it has to offer: "I'll work really hard. I’ll make double payments." That's what the servant asks for, but what does the King do? Does he grant the request? Does he agree to postpone the due date and let the slave try to work off what he owes? Not at all. He does something totally unexpected and, again, ridiculous: he forgives the entire debt. He absorbs 100% of it himself. Stop and notice that before we go on. The king decides not to collect what he’s owed, and absorbs all the ten billion dollar debt himself. Your balance is zero, he says; and not only that, the billing computer has no record of you. It’s over. There just is no more owing. The cycle is broken, and the slave walks out a free man. Or at least he could have, if he had been paying attention. But he shows by his behavior that he has completely missed the radical act that had just happened. He may have heard the words of absolution, but he did not let them set him free. That slave got his whole account wiped clean, but he acted as if it were only a payment holiday. All the interior guilt and striving is still there. He still feels the weight of his debt. How do we know? Because that's how he treats the next person he meets. The man he comes upon on the way out happens to owe him 100 denarii, about three months' pay. And before you can blink, the first slave is demanding payment from the second one. Forgiven ten billion, and still obsessing about a few thousand. His compatriot won't pay, well then, give him what's coming to him. Off to jail. But the real prisoner is that slave. He has remained captive to the hopeless cycle of trying to pay his own way, of keeping tabs on who owes what. And as it turns out, the king eventually lets him choose to stay there. The slave has not allowed forgiveness to break the cycle. The bookkeeping, the owing, the oughts are still at work. He didn’t really notice what the King did for him. And this probably is the central point of Jesus’ parable. Because we too are prisoners of the bookkeeping cycle with all its oughts, we misunderstand a lot of parables as being about what we ought to do. Here, we want Jesus to be saying that we ought to be more forgiving. But Jesus’ parables are almost never about what we ought to do. They’re about what God is like, and how what God is like changes the way we see reality. What Jesus wants is not for us to add another ought to the same old list, just one that happens to be religious this time. No, he wants us to notice what God has done for us, and be so stunned by the magnitude of the good news that we can’t help reacting. I don’t know why we find it as hard as we do to notice, especially when the owing and oughting system we’re in actually works so poorly and causes so much misery. We're not even free from it in church half the time, because often we haven’t noticed what God has done for us. We don't really believe in grace. We only believe in payment holidays, and then it’s back to settling accounts. Grace comes to people who give up on settling accounts, who have noticed the ludicrous generosity with which God has already absorbed our unpayable debt. Some of us may have memorized the definition "grace is God's undeserved favor." But that's not the half of it. Grace is God's favor which cannot possibly ever be deserved. Grace is a gift which cannot possibly ever be repaid. By definition. Because grace is what finally breaks the payment cycle. That's one reason I dislike the term "grace period." When you bring grace into a situation, there are no more periods. Grace wipes out punctuation. Grace throws the ledger out the window, and it's up to us to notice that it’s happened and let the thing go. The Episcopal Church has one of the most effective ways I know of to experience that power of forgiveness in the sacrament of reconciliation. In laying your life out before God in confession, you find out firsthand how freeing grace really is, and you see the squalid silliness of the payback system under which so many of us spend so much of our lives. You sometimes realize that you never knew what your real sins were at all. You may even discover that, in the words of today's Gospel, the brother or sister whom you must "forgive from your heart" is yourself. Sometimes I think that the most liberating and beautiful words in the English language are the ones that close the sacrament of reconciliation in the Book of Common Prayer. Sometimes those words have gone on ringing in my ears for days. "Go in peace; the Lord has put away all your sins." The cycle is broken. I cannot possibly communicate the exhilaration of that moment of encountering the God Jesus’ parable is trying to get us to see. And while you know in your bones how great a debt has been forgiven you, while you remember that heady feeling of how it was when God blew away all the rules you expected him to scold you for breaking, you will live free from the cycle. You will stop trying to collect. You will stop trying to pay your way. Because you will be in touch with how perfectly nonsensical the whole pathetic mess is, and what a glorious liberation God has already given us in his love, absorbing all the debt himself. And then you lose that, after awhile. The oughts begin to seem plausible again. The sense of owing and being owed creeps back in. But there’s always another parable coming along to remind you. There’s always another sacrament coming along to startle you awake. There’s always another scripture reading coming along to make you see reality. There’s always, always more grace. And you’re already preapproved.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed