In 1998 Robert Emmons, a psychology professor from UC Davis, designed a ten week research project with a colleague. It was one of those research projects psychology professors sometimes put their whole 101-level class through. Emmons later commented that after the results were published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, it became the most cited article in all his years of professional publication. This was how the experiment worked. About 200 students were randomly assigned to one of three tasks. Every week they had to describe, in a single sentence, either five things they were grateful for, or five hassles, or five events in their life. They then all filled out a variety of standard measurements of health and well-being, recording their mood, their physical symptoms, sense of social support, time spent exercising, and so on. Those who had to make a five-item gratitude list chose all kinds of things, for example: “my in-laws live only ten minutes away, it rained, my checkbook balanced, all the freedoms I have now that I live in the USA,” and my favorite: “The doctor removed ear wax from my ear.” The event lists were usually pretty neutral, including things like “I learned CPR” or “I cleaned my shoe closet.” The hassle lists are interesting, since they’re the kind of things that happen to us all every day and that you can convince yourself are terrible injustices if you focus on them: “it was hard to find parking, did a favor for a friend who didn’t appreciate it, having to buy a Mother’s Day card at the last minute, people who stand with their carts in the middle of the aisle at the store,” and my favorite: “my roommates are filthy animals.” When the results were tabulated, they were striking; and as I said earlier, the study became the most cited article Emmons has published in his career. Participants who had to notice and name things they were grateful for felt better about their life as a whole and were more optimistic about the future than participants in either of the other control conditions. When all the numbers got crunched, they were a full 25 percent happier than the rest of the group. They reported fewer health complaints and spent a whopping 30 percent more time exercising.

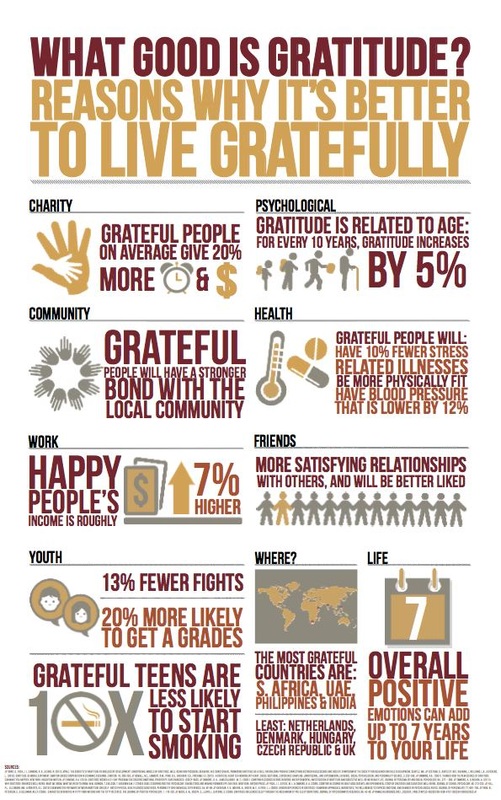

With funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the John M. Templeton Foundation, and the National Institute for Disability Research and Rehabilitation, Emmons continued his research: what if the subjects only made gratitude lists for 3 weeks? What if you did the same thing with participants who had a chronic disease? What if you did it with 80 year olds? What if you asked a spouse to report on the person’s mood and wellness, rather than the person to report on themselves? Though of course there were variations, all the studies showed some measurable wellness benefits to doing even a simple practice to cultivate a grateful attitude. Over the years the evidence piled up: stronger immune systems, lower blood pressure, lower lifetime risk for substance abuse, better sleep. It’s coming up on 30 years now, and Robert Emmons has become probably the world’s foremost expert on gratitude. He’s gone beyond researching what it does for your health into understanding how gratitude works and what larger attitudes and capabilities practicing gratitude builds in people. For example, gratitude is largely a relational emotion, requiring you to look outside yourself to see who or what has helped you, so it builds community and undermines narcissism. The connective aspect of gratitude also increases generosity to other: If you feel given to, you give. And gratitude turns out to be fairly morally complex, requiring dispositions that don’t come naturally to most people, as we saw in a couple of today’s readings. I don’t know how you would define gratitude, but Emmons has a great definition: “Gratitude is an affirmation of the goodness in one’s life and the recognition that the sources of this goodness lie at least partially outside the self.” The recognition that the sources of this goodness lie at least partially outside the self. This is something we affirm every Sunday at Emmanuel, in the one liturgical sentence newer parishioners ask me about more than any other. “I’ve looked everywhere,” they say, “I can’t find it! It’s not in the Prayer Book! What is it?” It is “All things come of thee, O Lord, and of thine own have we given thee.” This is a Bible verse from I Chronicles, and it’s a text that was in a previous edition of the Prayer Book, that for some reason never dropped out of the service here at Emmanuel. "All things come of thee, O Lord, and of thine own have we given thee." This sentence is associated with the offering plates. You know how that routine goes. It’s one of the most spiritually significant moments in the Mass: those plates gradually, as they move down the aisle from the altar and each of us puts something in, become the symbols of our resources, our livelihoods, our ability to earn a living, our ability even to be alive and participating in the Mass today, our time, our energy, our very selves. By the time the plates get to the back, all of that now fills them, which is to say that sacramentally, we are what fills them. And then, they turn back around, and come back up the aisle, carrying us with them, so that all that we are can be laid before Jesus in thanksgiving at the foot of the altar. All things come of thee, O Lord. The sources of all goodness lie at least partially outside the self. Of course there are people who disagree with that, who would claim that the sources of some goodness lie in us and us alone. That we created our own status and skills, we became able to make a living through our own hard work, and we deserve what we have. Very common opinion, of course. I think our earning power and skills are an area people very frequently try to make an exception to that “all things come of thee” verse, which is ironic if you’re an Emmanuelite, because our liturgy specifically tries every single Sunday to train us in the truth that there are no exceptions. All things come of thee O Lord and of thine own have we given thee. If you actually believe that and practice it regularly, according to Robert Emmons’ research, you will experience all kinds of benefits that folks who think they’re self-made are missing out on. At one point in his work, Emmons even talks about today’s Gospel reading, which he calls “Perhaps the most famous instance of ingratitude in history.” Ten lepers – the word means any serious skin disease – approach Jesus, calling out to him for mercy. And he says, “Go, show yourselves to the priests.” This comes from the Old Testament law in which, if someone went to the priest and could show that their contagious skin disease had resolved itself, the priest would certify that they were able to resume normal life without fear of infecting anyone else. So Jesus gives the ten lepers one simple thing to practice – up front, before any healing has happened. "Go show yourselves to the priests." It’s even easier than writing down five things you’re grateful for for a few weeks. So off these ten go, before any results are visible, and on their way down the aisle, all of them are healed. Luke the writer is very understated about it. He doesn’t say how God did it, he doesn’t show us the moment, but he sure shows us the one leper who responds with gratitude. Look at the verbs: he saw that he was healed, he turned back praising God, he prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet, and he thanked him. There’s a recognition – he sees that he has been healed and it penetrates. He recognizes what has happened. There’s a reversal; he changes course, turns around. He explicitly names what has happened – God did it. God healed me. And he expresses his thanks both physically and verbally directly to Jesus, showing that he gives Jesus the credit for God’s gift. He saw, he turned, he prostrated, he thanked. It’s not so different, by the way, from what we do with the offering plates – the recognition that all our gifts come from God, the reversal of direction so that the symbols of ourselves flow back up to the altar, and then the oblation before Jesus to give him the credit in grateful thanksgiving. Jesus responds to the healed man’s gratitude by delivering a speech, clearly aimed at the listening audience: “Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” The answer is obvious: Nope. They’re gone. They’re on to the next thing. You may think that it’s surprising that nine would be healed and not return and give praise to God, but after 20-plus years as a priest I think those numbers sound fairly typical. The human mind is highly ingenious in finding ways to take the credit away from God, to convince ourselves that the sources of our goodness lie inside us. That’s why we have to practice gratitude. It’s why we have to practice -- to take on a Lenten discipline of writing thank you notes, or keep a 10-week gratitude list, or calculate a percentage of our income to fill out a pledge card, or do a nightly Examen, or kneel by the bed and thank God like a child does. I’ll make sure a couple of Emmons’ suggestions for gratitude practice go up on our Facebook page, too. Because we’re all the 9 lepers. I know I am. Ever since the Fall, we all are. We’re all far too prone to take the credit, and far too prone to focus on our hassles rather than our blessings. We’re all the 9, saying, "Sure am glad I got that leprosy thing taken care of. That was smart of me." But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can practice gratitude, with all its benefits, and when we do reality will back us up, because Jesus has given us more to be grateful for than I could ever put into words. We can, at any moment, see his gifts afresh, turn around, and head back up to the altar, saying "All things come of thee O Lord, and of thine own have we given thee." Works consulted for this sermon: “What must we overcome as a culture or as individuals for gratitude to flourish?” accessed 10/4/2016 at https://www.bigquestionsonline.com/2013/11/11/what-must-overcome-culture-individuals-gratitude-flourish/ “Thanks! The science of Gratitude” accessed 10/4/2016 at http://cct.biola.edu/journal/article/2014/spring/emmons-interview/ The Emmons Lab webpage at http://emmons.faculty.ucdavis.edu/gratitude-and-well-being/ Gratitude Works, Robert A. Emmons (Jossey-Bass, 2013) Infographic: What Good is Gratitude? Accessed 10/4/2016 at https://www.templeton.org/grateful “Counting Blessings versus Burdens: An Experimental Investigation of Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being in Daily Life,” Robert A Emmons and Michael E McCullough, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2003, Vol. 24 No 2, 377-389

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed