|

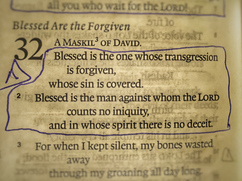

Earlier this year the popular website The Toast ran a feature called “Kind-Hearted Reality Shows I’d Like to See.” The author explained that after a hard day at work, she often found herself just wishing she could come home to something pleasant. She wrote “I don’t want to watch anyone fail, and I don’t want to watch anyone fight. I just want the reality-show equivalent of a… home-cooked meal, and to be reassured that not everything in the world is horrible, all of the time.” She had a list of suggestions for new reality shows that would fit this bill, like Your House Is Nice Just The Way It Is, in which “a decorating crew shows up at a house to praise its already charming features.” Or perhaps Back in My Day: “A famous actor heads to a retirement home and asks people to tell their favorite stories.” And then the final suggestion: Everybody Gets Prizes, a show where, well, everybody just gets prizes. I loved The Toast’s list, but it struck me that it’s no wonder reality shows like those don’t get programmed. Scandal, conflict, and violence grab people’s attention, and content creators have long since learned to take advantage of that. All our media over-exaggerate the prurient and attention-grabbing features of life in order to get a bigger audience so advertisers can sell more products. It’s one of the most effective and popular spiritual formation programs in America.  Although it’s much less popular, one of the striking things about reading the Bible is that, unlike either the Toast’s reality shows or TV’s reality shows, it reflects real reality. The Bible is certainly not Pollyanna inspirational literature; if the Motion Picture Association of America rated it as a film, the rating could only be R. But neither does Scripture exaggerate the evils of our world. It gives a perfectly realistic picture of who we are and what life is like – which is one of the ways we know that we can turn to it for honest guidance that works. Today’s Old Testament reading, and the Psalm that follows it up, are a perfect example. In this passage from 2 Samuel, the prophet Nathan is confronting King David. David, who is the golden boy to end all golden boys, has been in many senses a brilliant leader; he’s unified the 12 tribes of Israel into one nation – which, upon his death, we will quickly discover nobody else can hold together. He’s a composer and a poet; he’s a rich and powerful politician. But amidst all those strengths, there are also flaws eating away at him and cascading down into the family and systems he is part of. He is a man of larger-than-life appetites which sometimes control him more than he does them, and he has very few checks and balances on how he uses his power. He unified the country, but his own family is a mess, struggling with all kinds of estrangement, dishonesty, and backstabbing. There’s even abuse of one of the daughters, which David enables. And it’s not like he has a clean record on that front himself, which is where today’s reading comes in. I said that Nathan was confronting David in this story. Here’s what the confrontation is over. On a whim, David has misused his power to force one of his subjects, Bathsheba, to sleep with him. She gets pregnant; and his main concern is not her, but getting found out himself. Bathsheba is married to Uriah, who is a Hittite, an ethnic minority, but he’s away serving in the Israelite army. So David tries to cover up his sin via giving Uriah a furlough to go visit his wife. That part of the story is a bit uglier than I’m telling you, because I’m in the pulpit. I love the fact that the Word of God is so honest that a preacher can find herself wondering if what it actually says may be a bit too much for church. Anyway, Uriah is such a man of character that he won’t take advantage of the opportunity. So what does David do? Does he look at the noble, loyal Uriah and think, “David, why not emulate him. Be a man; make things right”? No, he just has Uriah murdered. Makes the arrangements, completely premediated, writes out the instructions, Uriah’s dead. And again, I won’t go into it, but the details are as ugly as they come. No wonder our text this morning says, with I think not a little understated irony, “The thing that David had done displeased the Lord.” So here’s how the Lord handles that. He sends the prophet Nathan to David, and asks him to tell him a story. And Nathan does. He tells David his own story, but with the names changed, as if it were about someone else. A man did this, and then the man did that, and then this other thing… A tale of abuse and greed. And David responds with the fascination and outrage of any reality TV viewer: “No way! How could someone behave like that! We can’t let the man get away with this!” Whereupon Nathan coolly replies: “You are the man.” As David hears God’s point of view on what he has done, a word from the outside that lets him see himself as God sees him, his heart is pierced. To his credit, despite being a person who abuses power, despite being proud – David is also someone who can receive this Word from God, and he repents. No excuses, no cover-ups, no blame of anyone else. One clean, honest sentence. David says, “I have sinned against the Lord.” If you can say that, there is hope for you. The sins David engaged in, and the sickness and lies that cascaded down from them into the systems he was part of, are honestly depicted in the Bible. Yet so is David’s thirst for God, which was never quite killed off by his sin. There was still some window inside him for grace to come through with that clean, straightforward statement of truth: This is what you have done, David. This is how God sees you. And David was able to agree with God. Yes, that is what I did. It was wrong. It was my fault. We don’t know for sure when David wrote the Psalm we prayed this morning, Psalm 32, but it and Psalm 51 are sometimes associated with the story of David facing up to what he did to Bathsheba and Uriah. The Psalm says “while I held my tongue, my bones withered away… but then I acknowledged my sin” and goes on to describe the liberation and joy that come with confession. David does not become a perfect person – again, the Bible has no rose-colored glasses, and I sure wish we knew Bathsheba’s side of the story and more about how David followed through with her after his admission of guilt and how God ministered to her – but I do think we see signs in the next few chapters of how the grace of this moment impacted David. And we see it in Psalm 32. Psalm 32 shows that when we agree with the story God is telling about us, and speak the truth back to him, God meets us not with condemnation, but as our ever-present guide (v. 9), the one who embraces us (v. 11), and our deliverer who gives us rejoicing and gladness (v. 12). Confession means to agree with the way God sees what you have done, to tell the whole truth of your story without excuses or blame, and to be ready to make things right. And when we verbalize ourselves that way to God, either alone or in the presence of a priest in sacramental confession, what Psalm 32 documents happens – healing comes. We start to move from dryness and paralysis to being moved by mercy. This is how working through the truth, in the presence of God, about what you’ve done -- and what’s been done to you -- is. This is the human process that Scripture is wise enough to depict. Whenever we grapple with the actual text of the Bible, we discover how insightful it is about us. And how timely. I mean, these readings are straight out of our headlines. Our nation is having conversations right now about the issues they address – about how powerful politicians treat women and minorities, and about who gets off easy for abusive behavior and who doesn’t. Scripture is no stranger to these kinds of conversations. It gives realistic input on how God sees sin, how he speaks, how he heals, what happens when you go against the grain of the reality that he designed, and what happens when you shift to go with it. Scripture speaks powerfully into the real world where people are sinners and where God is both absolutely just and absolutely merciful. If you throw either side of that paradox about God away, you get in trouble. A God with no justice would be a sentimental fiction who lets us be spoiled children and lets evil have its way. A God with no mercy would be a moral tyrant whom we couldn’t love. Neither reflects the way life actually is. But a God who is both utterly just and utterly merciful, that is who we see in Scripture. Not a Pollyanna, not a power-monger, not a pious fiction, but the source and summit of everything we’re looking for to understand who we are and how the universe works. If we are open to it, he will reveal in all kinds of ways, bit by bit, what life is and who we are. What we have done. What has been done to us. And even if we’re not open, God will keep trying to tell us our true story, with more justice, mercy, and insight than anyone has ever told it. May we, and all who have sinned, and all who have been sinned against, learn what it is to listen to his voice. Amen.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed